Do I Need to Take the Sat Again to Go Back to School

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ff/75/ff75e9ac-e0d0-446d-b4f3-187d2597fe9f/gettyimages-1231910406.jpg)

Clara Chaplin had studied. She was ready. A inferior at Bethlehem Primal High School in Delmar, New York, she was scheduled to have the Sat on March fourteen, 2020. Then the pandemic hit, and the exam was canceled.

The April Sat was canceled too. All through the spring and summer and into the fall, every examination date she signed up for was either full or canceled. Every bit she submitted her college applications on November ane, she nonetheless didn't know how she'd score on the SAT she finally would manage to take on November vii.

Many students never made it through the test-center door; the pandemic left much of the high school grade of 2022 without an SAT or ACT score to submit. Facing test admission challenges and irresolute application requirements, nigh half did not submit scores with their applications, according to Robert Schaeffer, executive managing director of the nonprofit National Middle for Off-white & Open up Testing in Boston. This didn't bar them from applying to the nation's nigh selective colleges equally information technology would accept in any other year: Starting in jump 2020, in a trickle that became a deluge, the nation's most selective colleges and universities responded to the situation by dropping the standardized test score requirement for applicants.

Liberal arts colleges, technical institutes, historically blackness institutions, Ivies — more than 600 schools switched to test-optional for the 2020-21 application season, and dozens refused to consider test scores at all.

"That is a tectonic modify for many schools," says Rob Franek, editor in primary of the Princeton Review, a test-prep company based in New York City.

The pandemic sped up changes that were already afoot; even before Covid, more than ane,000 colleges had fabricated the tests optional. Many had been turned off by the way the tests perpetuate socioeconomic disparities, limiting their ability to recruit a diverse freshman class. Some groups of students, including those who are Black or Hispanic, non-native English language speakers, or depression-income, regularly score lower than others. And students with learning disabilities struggle to get the accommodations they need, such as extra time, to perform their best.

Ironically, some early proponents of testing had hoped it would level the playing field, past measuring all students with the aforementioned yardstick no matter their groundwork. That goal was never fully realized, only the tests persist because they practice correlate to some extent with college course indicate averages, offering schools an like shooting fish in a barrel manner to predict which students will perform well once they matriculate.

The benefits and risks of testing — existent and perceived — have fueled an ongoing, roiling debate among educational scholars, admissions officers and college counselors, and the yr of canceled tests gave both sides plenty to chew on. "The contend out there is peculiarly divisive right now," says Matthew Pietrefatta, CEO and founder of Academic Arroyo, a test-prep and tutoring company in Chicago.

As the pandemic wanes, some advocates for disinterestedness in higher ed hope that schools realize they never needed the scores to begin with. The virus, Schaeffer says, may have made the indicate better than three decades of inquiry indicating the feasibility of test-free admissions.

But others, including test-prep tutors and many educators, are apprehensive about the loss of a tool to measure all students the same way. Standardized tests, they say, differ from high-schoolhouse grades, which vary from schoolhouse to schoolhouse and are ofttimes inflated. "In that location is a place for testing in higher ed," says Jennifer Wilson, who has years of experience as a private test-prep tutor in Oakland, California.

In a post-Covid world, the challenge is to figure out what, precisely, that place should be.

An evolving yardstick

Testing in U.Due south. college admissions goes back more than a century, and issues of race and inequity dogged the process from the become-go.

During the belatedly 1800s, elite universities held their own exams to assess applicants' grasp of college prep material. To bring order to the admissions process, leaders of aristocracy universities banded together to develop a common test, to exist used by multiple leading universities. This produced the first College Lath exams in 1901, taken by fewer than 1,000 applicants. The tests covered 9 areas, including history, languages, math and physical sciences.

In the 1920s, the focus of admissions tests shifted from assessing learned fabric to gauging innate ability, or aptitude. The idea for many, Schaeffer says, was to find those young men who had smarts but couldn't afford a prep-schoolhouse teaching. That led to the 1926 debut of the College Board's original Scholastic Aptitude Exam, which was spearheaded by Princeton University psychologist Carl Brigham. Across-the-board equality wasn't exactly the goal. Brigham, who also saturday on the advisory quango of the American Eugenics Society, had recently assessed the IQs of armed services recruits during World War I, and opined that clearing and racial integration were dragging down American intelligence. (Brigham later recanted this opinion and broke with the eugenics movement.)

The SAT was widely taken upward in the years following Earth War II as a way to place scholarly aptitude among returning soldiers seeking to use the GI Pecker for their studies. Then, in the 1950s, University of Iowa professor of education East.F. Lindquist argued that it would be better to assess what students learned in schoolhouse, not some nebulous "aptitude." He designed the Human activity, first administered in 1959, to match Iowa high school curricula.

Today, the Human activity includes multiple-selection sections on English, math, reading and scientific discipline, based on nationwide standards and curricula. The Sabbatum, which is split into ii parts covering math and reading and writing, has likewise adopted the strategy of assessing skills students larn in school, and admissions officers have come to consider SAT and Human activity scores interchangeable.

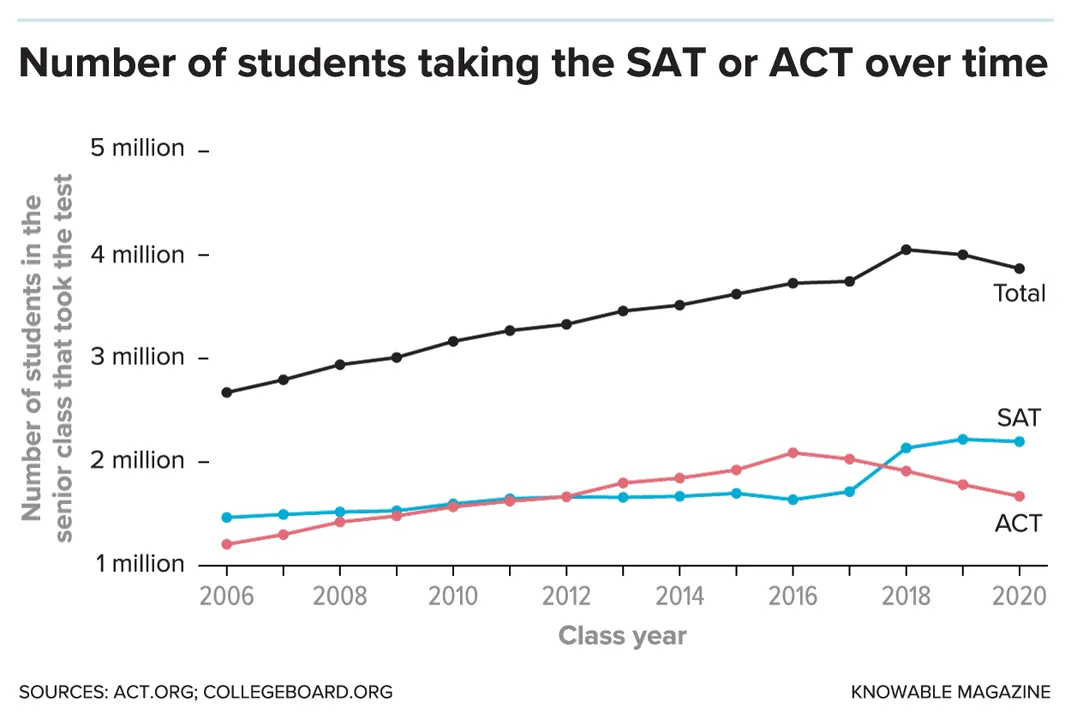

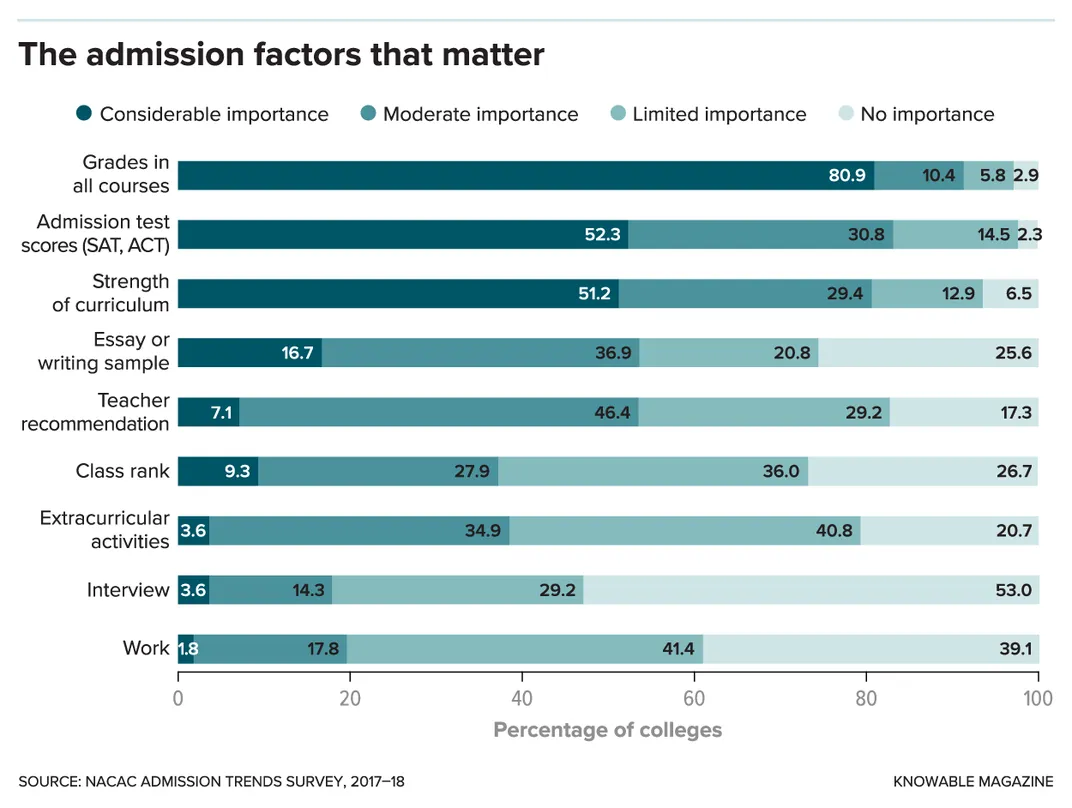

Until the pandemic, scores from i exam or the other were required by more than half of U.S. four-year institutions. Among the high school class of 2019, more than than two million students took the SAT and well-nigh 1.eight 1000000 took the ACT. Along with grades and courses taken, examination scores topped the list of factors of import to admission offices in pre-pandemic times, and were often used as a convenient cutoff: At some universities, candidates below a certain score weren't even considered.

What are we really measuring?

The very endurance of the test market speaks to the SAT'due south and Act's perceived value for college instruction. People in the manufacture say the tests address higher-relevant skills in reading, writing and math. "Tin can you edit your own writing? Tin can you write compelling, clear, cogent arguments? This is near a larger gear up of skills you're going to need for college and career," says Pietrefatta of the exam-prep company Bookish Approach.

Not that universities accept the tests' value for granted. Many schools have assessed what testing truly gives them, generally finding that higher scores correlate with higher first-year college GPAs and with college graduation rates. The University of California, a behemoth in college ed with more than 280,000 students in its x-campus system, has considered, and reconsidered, the value of testing over the past two decades. In the almost recent analysis, completed in January 2020, a kinesthesia squad plant that both high school GPA and test scores predicted college GPA to a similar degree, but considered together, they did even better. Last that the test scores added value without discriminating against otherwise-qualified applicants, in April 2022 UC's Academic Senate, made up of faculty, voted 51-0 (with one avoidance) to reinstate the testing requirement once the pandemic subsides.

Just later that spring, UC's governing board unanimously overruled the faculty, making the tests optional due in large part to their perceived discriminatory nature. A lawsuit brought by students with disabilities and minority students later drove UC to ignore all examination scores going forward.

Even if exam scores can predict higher grades, admissions officers are looking for more than that. They seek young adults who will use their education to contribute to society past tackling of import challenges, exist they climate change, pollution or pandemics. That requires creativity, problem-solving, insight, self-subject and teamwork — which are not necessarily taught in schools or gauged by standardized tests.

There are ways to test for those qualities, says Bob Sternberg, a psychologist now at Cornell Academy in Ithaca, New York. In a 2006 study sponsored past the College Board, maker of the Sabbatum, he and his colleagues tried to predict college GPAs meliorate than the SAT alone tin can practise past adding assessments of analytical, practical and creative skills. To measure out creativity, for example, they asked students to provide captions for New Yorker-mode cartoons and to write short stories based on titles such equally "The Octopus's Sneakers." They constitute that by adding the extra assessments, the researchers doubled their ability to predict higher GPA. Student scores on the additional test materials were also less likely to correlate with race and ethnicity than the standard Sat.

Sternberg put these ideas into exercise in a previous position he held, every bit dean of arts and sciences at Tufts Academy, by adding additional, optional questions to the university'due south application class. "When you use tests like this, y'all detect kids who are really adaptively intelligent in a broader sense, but who are not necessarily the highest on the SAT," he says. And when those students came to the university, he adds, mostly "they did groovy."

The real problem with testing

The question at the heart of the testing debate is whether relying heavily on the SAT and ACT keeps many students who would do well at college, particularly those from disadvantaged populations, from ever getting a shot. The 2022 UC faculty written report establish that demographic factors such equally ethnicity and parental income also influenced test scores. "If you want to know where people'due south zip codes are, utilize the Sat," says Laura Kazan, college counselor for the iLead Exploration charter schoolhouse in Acton, California.

When poor, Blackness or brownish students score lower, it's non exactly the tests' fault, says Eric Grodsky, a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison who analyzed the links between standardized testing and socioeconomic status in the Annual Review of Folklore. That's because scores reverberate disparities in students' lives before testing. Wealthy students, for example, might have benefited from parents who had more time to read to them as toddlers, all the way through to beingness able to afford to take both tests, multiple times, to obtain the best score.

Other kids might not fifty-fifty exist aware they're supposed to have a exam or that information technology's something they can prepare for, says James Layman, managing director of the Association of Washington Educatee Leaders, headquartered in Randle, Washington. Students from poorer schools tell him they often don't hear virtually test prep or other opportunities, or they lack the time to have advantage of them because they're busy with jobs or caring for younger siblings. To endeavor to level the field, in 2022 the College Lath teamed upward with the nonprofit Khan University to offering free online Sabbatum prep materials, but even that requires an Internet connection at home and the time and space to have advantage of the programme.

Thus, the disparities reflected in test scores result not from a failure of the tests so much as a failure to create a merely educational system, Grodsky says. "We don't exercise a good job of serving all our kids." And if examination scores determine one's future opportunities, using them can perpetuate those inequities.

That suggests that admissions officers should, perhaps, turn to loftier-school grades. Merely those are fraught with their ain set of issues, such as aggrandizement. In one example, a recent study tracked algebra grades at North Carolina schools for a decade and reported that more than one-third of students who got a B in Algebra weren't even rated "expert" in the subject on a state test. Moreover, between 2005 and 2016, boilerplate GPAs at wealthy schools rose by 0.27 points, compared to just 0.17 points at less affluent schools.

Of course, wealth and demographics also influence access to other pre-higher resources, such equally advanced coursework and extracurriculars. Merely ranking applicants by test scores is specially likely to put people of certain races on the top or the lesser of the listing, argued Saul Geiser, UC Berkeley sociologist and former director of admissions research for the UC organisation, in a 2022 article.

Conspicuously, the tests aren't all good, or all bad. There's a lot of nuance, says Pietrefatta: The tests offering value in terms of the skills they assess and the predictions they make, even as they remain unfair to certain groups of people who haven't been positioned to principal those skills. This leaves colleges that value both diversity and well-prepared freshmen trying to strike a delicate, possibly impossible, balance between the two.

Edifice a class, test-gratuitous: Admissions in Covid times

The pandemic forced a number of universities to rebalance their approach to admissions, leaving them no choice but to experiment with ditching standardized tests. And the results weren't then bad.

Name-brand schools similar Harvard experienced a massive fasten in applications. The UC system saw applications for fall 2022 access balloon by 15 percent over those for 2020. At UC Berkeley and UCLA, applications from Blackness students rose by well-nigh 50 percent, while applications from Latinos were up by nigh a 3rd.

To choose among all those college hopefuls, many institutions took a holistic approach — looking at factors such as rigor of high school curriculum, extracurriculars, essays and special circumstances — to fill in the gaps left by missing examination scores.

Take the case of Wayne State University in Detroit, where before Covid, high school GPA and standardized test scores were used as a cutoff to hack 18,000 applications down to a number the university's 8 admissions counselors could manage. "Information technology was just easier," says senior manager of admissions Ericka Chiliad. Jackson.

In 2020, Jackson'south team inverse tack. They made test scores optional and asked applicants for more than materials, including short essays, lists of activities and evaluation past a high schoolhouse guidance counselor. Assessing the extra textile required assistance from temporary staff and other departments, but it was an center-opening feel, Jackson says. "I literally am sometimes in tears reading the essays from students, what they've overcome … the GPA can't tell yous that."

Many students were thrilled that they didn't have to take standardized tests. At the iLead Exploration charter school, terminal year's college hopefuls included several who may not take fifty-fifty applied in a normal year, Kazan says. "There were so many people that came to me, so happy and so excited, and and then eager to utilise to college, when before they were in fright of the test." And when the admissions letters came in, she adds, the students had "phenomenal" success. Seniors were admitted to top schools including UCLA, USC and NYU.

The road alee

Kazan has loftier hopes for the senior grade of '22, too, and won't be pressuring anyone to sign up for a standardized test, fifty-fifty if exam dates are more accessible equally the pandemic wanes. That's because many institutions program to see how test-optional admissions become, for a year or more, earlier reconsidering the value of the tests. More than than 1,500 of them take already committed to a examination-optional policy for the upcoming admissions flavour.

For hints of what'southward to come if they go along along that route, admissions officers can look to schools that have been exam-optional for years, even decades.

Bates College in Lewiston, Maine, dropped the SAT requirement in 1984, asking for culling exam scores instead, before making all testing optional in 1990. In 2011, Bates took a look back at more than two decades of test-optional admissions, and how enrollees fared afterwards they came to college. Dropping the test requirement led to an increment in the variety of Bates's applicants, with major growth in enrollment of students of color, international attendees and people with learning disabilities. Once those students reached college, the achievement departure between students who submitted exam scores and those who didn't was "negligible," says Leigh Weisenburger, Bates's vice president for enrollment and dean of admission and financial assistance. Those who submitted test scores earned an boilerplate GPA of 3.16 at Bates, versus iii.xiii for non-submitters. The difference in graduation rates was only one percent.

The mural will be forever shifted by the events of the pandemic, says Jim Spring, academic dean and manager of college counseling at St. Christopher's Schoolhouse in Richmond, Virginia. "The toothpaste is not going back in the tube." 1 big factor, he says, is the fact that the University of California won't look at exam scores anymore. That ways many California students won't bother to take a standardized examination, Spring says, making information technology hard for schools hoping to recruit Californians to require them.

There will, of course, be holdouts, he adds: The near elite, selective schools may exist immune to that pressure. And universities that receive lots of applications might go back to a examination-score cutoff to bring the pile of applications downwards to a manageable number, saving on the time and effort that holistic admissions entail.

The ultimate solution to the dilemma may lie in flexibility. "I retrieve information technology should exist optional from now on," says Chaplin, who was fully satisfied with her SAT score after she finally managed to have the examination, and is headed for highly ranked Bucknell Academy in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. This would allow strong test-takers to shine but also let applicants showcase other strengths.

Students at the Association of Washington Student Leaders agree, Layman says — they don't think exam scores truly reverberate who they are.

"At that place are other means," they tell him, "for colleges to get to know us, and usa them."

Knowable Magazine is an independent journalistic endeavor from Annual Reviews.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/has-pandemic-put-end-to-sat-act-180978167/

0 Response to "Do I Need to Take the Sat Again to Go Back to School"

Postar um comentário